Listening is a Movement

Lines of Listening: A Somatic Series on How We Hear, Move, and Understand

To borrow from philosopher John Shotter, this movement in listening is a kind of withness. Shotter writes that human meaning is not fixed or self-contained. Instead, it is emergent, relational, and alive. “What is of importance to us exists not only in relation to what else is around it and us,” he says, “but also in our sense that there is always a something more beyond it” (Shotter, 2015, p. 232). Listening in withness is listening with the moment — with the shifting context, the body of the other, the air in the room. It is not “aboutness” — not categorizing or summing up — but being present with what is still unfolding.

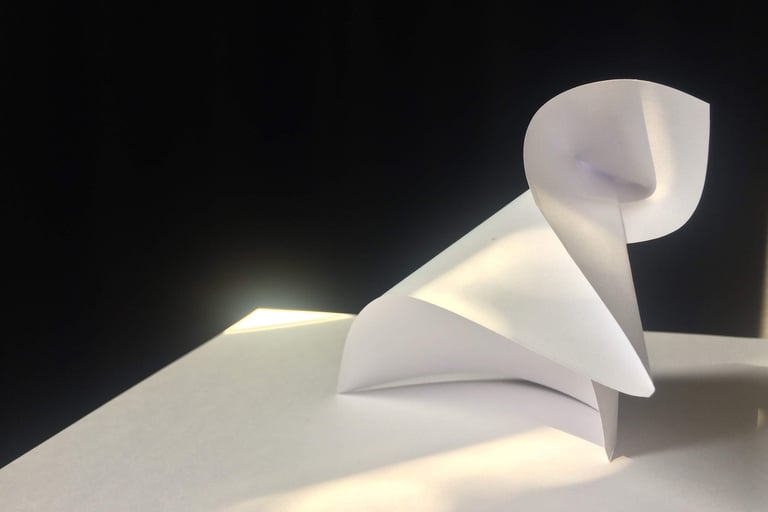

When we listen this way, we move beyond passive reception. We listen with direction — intendere, from the Latin, meaning to aim, to point, to stretch toward. This is the same root that gave French two different meanings: entendre (to hear or understand) and tendre (to stretch). The etymology itself reminds us that hearing and stretching are linked: to listen is to aim our attention outward, to engage our full selves.

Just like in the tendu, this stretch also brings a fold. But where does the fold occur in listening? In movement, the fold is felt in the body’s joints — the hip, the shoulder, the spine. In listening, the fold might appear as a pause, a reorientation, a moment of insight. It may be the way our thoughts reorganize in real-time, in response to what we are receiving. Listening begins with reaching, but meaning is made in the return — in the fold.

As philosopher Deleuze notes, different materials fold differently (1992, p. 34). So too do different bodies, different contexts, different listeners. There’s no single fold in listening, no singular meaning that snaps into place. Instead, there is a mutual shaping — between speaker and listener, between motion and pause, between line and response. The dancer doesn’t think, “I must fold my hip.” The fold happens because they extend. Listening works the same way: something shifts because something reaches.