Movement as a Way of Remembering

Mike O'Connor

9/8/20253 min read

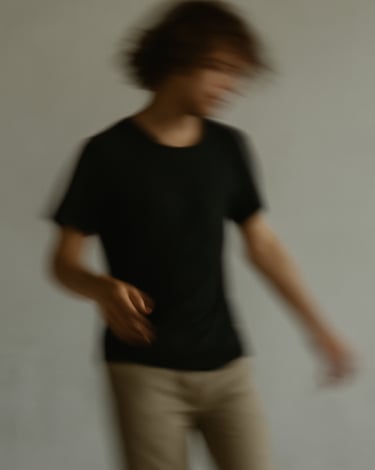

We often think of memory as something held in the brain — a fact recalled, a date retrieved. But movement, too, is a form of memory. The body remembers — in sensation, in gesture, in posture. In my work, I return again and again to this: that movement is not only expression but a kind of archive — a personal and collective history stored in shape and motion.

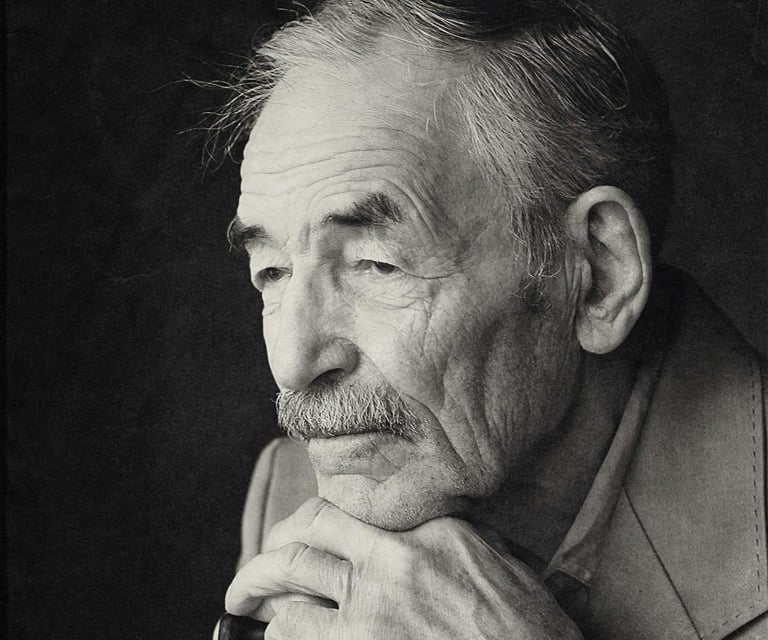

Michael Leyton, a scholar who spans art, mathematics, and philosophy, writes that “shape is the means of reconstructing history.” He describes how a crack in a vase or a wrinkle in a face holds the story of an event — an impact, a smile, a stretch of time. “Shape is the means by which past actions are stored,” he says. This idea, that asymmetry contains memory, has become a lens through which I view both movement and identity.

A dancer’s curved spine, the bending of a tree, or the fold of a wrist mid-gesture, these shapes hold echoes of previous moments. The wind blows a napkin across the concrete. The linear trace of the tumbling, papery object, folding and unfolding over itself, has latent pauses and sharp, dynamic bursts when it unsticks itself from crevices in the concrete. The immediate trace that is observed holds the memory of how the napkin may move in the future. The napkin’s paths and projected paths are sensed. I imagine these trajectories. We intuit its past and predict its future. We don’t just watch it move — we feel its memory.

The Body Knows What We Forget

In somatic bodywork, I’ve witnessed how bodies recall what words cannot. A hand begins to tremble as it extends. A chest tightens when touch is placed on the body. Clients are often surprised: “I didn’t know I remembered that.” But the body knows. It stores impact, just like the crack in the vase.

This is especially true in queer life. For many of us, our movements were shaped before we understood why — gestures hidden or exaggerated, voices modulated, bodies made smaller or flamboyantly larger. Queer memory is not only found in words or archives. It is also found in the way we walk into a room, how we carry desire, fear, protection. Movement becomes a way of tracing ourselves back — and forward.

Traces in Motion

Scribbles, theorist says, aren’t meaningless. They are traces that stimulate further actions, a kind of feedback loop of sensation and motion. Cognitive archaeologists point to ancient carvings in caves not simply as messages, but as acts of meaning-making. They argue, the drawings reveal how the body thinks — not just what it thinks about.

The shape of a tree tells us how it grew. The shape of a person’s face tells us something about time, tension, expression. And just as gravity bends space-time, Leyton argues that curvature itself becomes a record of force. We might say, that our own bodies — with all their curves, asymmetries, and hesitations — are bent by the forces we’ve lived through.

When I walk along a landscape, I think about how I’m shaping it and how it’s shaping me. The lines I trace are informed by the slope, the cracks, the resistance of the earth. Like a potter’s hand shaping clay, there’s a feedback loop between intention and material.

Curves of Force and Time

We can begin by moving slowly. Noticing not only what we do, but how it feels. We can track the folds, the hesitations, the asymmetries — and wonder what stories they might be holding. We can treat our gestures not just as expressions, but as invitations to remember. They are qualities—aesthetic memories. To feel what came before. To connect with a lineage, even if we don’t know its name.

For queer people, for neurodivergent folks, for anyone who’s had to shapeshift to survive — movement offers a quiet return. A re-membering. A way to be in the present without leaving the past behind.