The Shape of Unfinished Things

A series on ambiguity, flow, and formlessness — Part 2

Mike O'Connor

11/3/20252 min read

What happens when something doesn’t resolve? When a line doesn’t end in a shape, when an image never quite becomes a picture, or when a sound drifts without settling into melody? These unfinished forms, rather than being failures of completion, can serve as openings.

As I explained in the first part of this series, ancient cave drawings sometimes merge one figure into another—a boat becoming a bird, an elk transforming into a vessel—to preserve something in motion. But ambiguity in these cases isn't only about blending; it’s about withholding finality. In this second part, we turn toward unfinishedness—not merely as a visual trick or symbolic strategy, but as a lived and perceptual state.

Meaning without Arrival

Unfinishedness resists closure. A line that breaks off mid-gesture can still carry weight. A movement that doesn't resolve may still convey something deeply felt. We are conditioned to seek completeness, to fill in gaps, to tie threads into form. But in perception itself—sometimes the strongest or deepest insight is what remains open. Unfinishedness holds space for resonance.

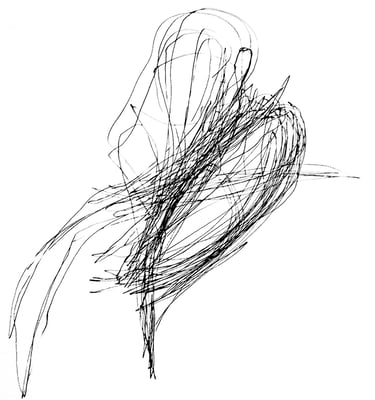

In my own research, I noticed how practitioners working with lines—in drawing, dancing, or sculpting—often don’t begin with a form in mind. The line doesn’t represent; it becomes. It gathers sense through its unfolding, not its arrival. Rudolf Arnheim reminds us that visual meaning is not static: it forms through resemblance, through rhythm, through the repeated nearness of things. The shape of an unfinished thing allows the viewer—or listener, or mover—to meet it halfway. It becomes not a delivery of meaning, but a proposal.

Unfinished, Not Undone

Unfinishedness can feel uncomfortable. We want to conclude, to make sense, to say what it all meant. But in practices that honor ambiguity—from artistic improvisation to somatic work—it’s often the open edges that create the most lasting connections. When the body moves without trying to finish a phrase, it’s not incomplete, it’s listening. When touch happens without a goal, it’s not vague, it’s alive to what else might emerge. These forms of unfinished action are not passive; they are invitational.

The shape of unfinished things is a living shape. It doesn’t demand to be defined. It doesn’t close itself off. Instead, it makes space for meaning to arise, for perception to participate, for others to come close.

Ambiguity, then, becomes a mode of withness—a term from philosopher John Shotter, who describes our ability to think and act from within unfolding situations, guided not by fixed meaning but by felt sense. He writes that “we are seeking to resolve what we at first encounter as an indeterminate, ambiguous, or bewildering situation by our active inquiries within it.” This echoes what Tilley and Arnheim show us visually: that resemblance is not a conclusion, but a beginning.

In this sense, ambiguity is not a temporary lack of clarity but a method for staying present with meaning as it forms. We don’t need to resolve uncertainty in order to engage with it. Sometimes, the power of a thing is precisely in its unfinishedness.