Why I don't believe in Self Love

Sorry but RuPaul is wrong

Mike O'Connor

6/6/20254 min read

In the age of pop-psychology and self-help mantras, few phrases get tossed around as frequently or as vaguely as "self-love." From Instagram quotes to wellness workshops, we are told that self-love is the foundation for everything: health, happiness, relationships, success. But what if this is not only misleading—but potentially harmful?

As a somatic therapist and movement practitioner, I have spent over 25 years immersed in the relationship between body and mind. My PhD research investigated the neuroscience, psychology and phenomenology of how we understand each other. I also lead retreats and work with people navigating trauma and transformation. And I want to say something that often goes unspoken: I don’t believe in self-love.

This isn’t to say I don’t believe in care, healing, worthiness, or personal growth. But the idea that love is something we can simply generate for ourselves in isolation runs contrary to what we know about how human beings actually develop and regulate emotionally. Love, at its core, is relational.

The Need to Be Loved First

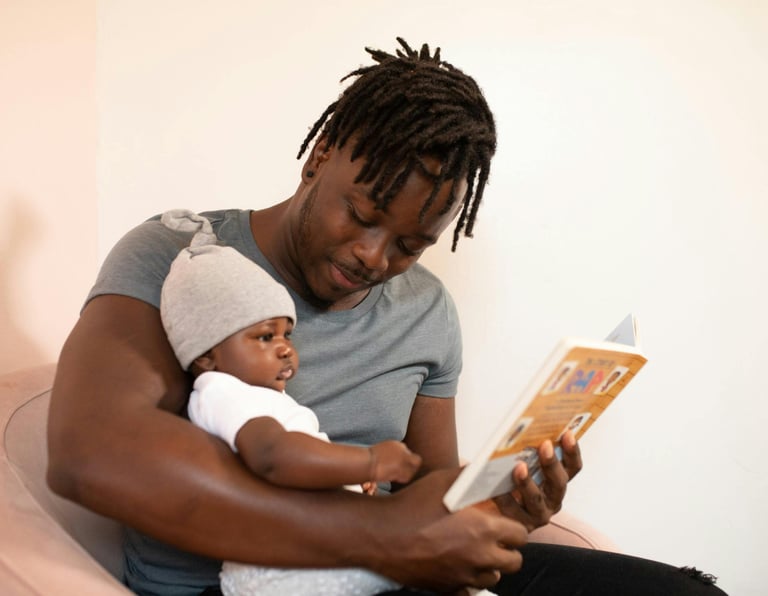

Neuroscientist and trauma expert Dr. Bruce Perry puts it simply: "You need to be loved before you can love." Our brains are shaped through interaction. Hormonal bonding, neural regulation, and emotional attunement all occur in relationship. The notion of self-generated love ignores that our ability to feel safe, worthy, and connected comes from others first. This isn’t just psychological—it’s physiological.

When someone hasn’t had that foundation, they often search for it later in life through self-love. But here’s the problem: if love wasn’t modeled or felt in the nervous system early on, then the pursuit of self-love in isolation can become a kind of double bind. You’re being asked to generate something internally that you’ve never experienced externally. This can lead to confusion, shame, and the feeling that even your attempts at personal development or healing are failing.

Self-Love or Self-Compassion?

What many people call self-love is often more accurately described as self-compassion, self-respect, self-worth or self-acceptance. Psychologist Kristin Neff, who pioneered the field of self-compassion research, is frequently cited in self-love rhetoric. But her work is careful to distinguish self-compassion from self-esteem or narcissism. Her practices are about gentle awareness, not feel-good affirmations or self-indulgence.

Similarly, in attachment theory, our capacity for emotional regulation and self-worth is internalized from relationships. The so-called "inner child" doesn’t become secure because we tell it to love itself. It becomes secure because it was loved, mirrored, and held. Without that, the burden of creating inner safety and worth can be overwhelming.

Philosophical and Theoretical Echoes

The view that love is fundamentally relational is not new.

Martin Buber, in I and Thou, explains that love exists in the space between two people—in encounter, not in isolation.

Simone Weil suggested that love is an act of attention toward another.

Judith Butler, from a queer ethical perspective, warns against making emotional and moral development a private, internal affair when it's deeply shaped by social contexts.

Even modern thinkers like Tara Brach, who use the phrase "radical self-love," are often describing a process of nonjudgmental awareness and presence, not affection to one's self in the traditional sense. The term often serves as shorthand for wholeness or integration, not hormonal bonding or attachment repair.

The Risks of Isolated Self-Love

The danger here is twofold. First, for people in crisis, being told to "just love yourself" can feel invalidating. It reframes the lack of relational support as a personal failure. Instead of recognizing the legitimate absence of love in one’s life, the burden is placed back on the individual to manufacture it internally. This can create a cycle of self-blame and stagnation.

Second, when misused, self-love rhetoric can become egocentric. People may use it as an excuse for selfishness, avoidance, or even emotional neglect of others: "I'm setting boundaries" becomes a cover for dismissiveness. "I'm putting myself first" becomes a justification for entitlement. Without a relational anchor, self-love can drift into a kind of spiritual bypassing.

A More Grounded Alternative

Instead of chasing self-love, we might focus on self-trust, earned confidence, and relational repair. Rather than pretending we don’t need others, we can acknowledge that part of our healing requires connection. It’s okay to need to be loved. We can foster self-compassion, yes. We can practice attunement to our bodies and emotions. But we should stop pretending that love is something we do alone. So sorry, RuPaul, we CAN simply love others and hope to be loved in return.

Sometimes the most honest, healing thing we can do is to admit we’re still waiting to be loved the way we needed. And maybe, healing begins there—in truth, not in slogans.

"The truth is, you cannot love yourself unless you have been loved and are loved. The capacity to love cannot be built in isolation. Relationships are the agents of change and the most powerful therapy is human love." Dr. Bruce Perry